Targeted Nutrition: Oxalates

What are oxalates?

Oxalate is a naturally occurring molecule found in abundance in plants and humans. It’s not a required nutrient. In plants, the compound oxalate helps to get rid of extra calcium by binding with it; this is why high-oxalate foods are from plants.

Why is oxalate important?

Oxalate content in the diet has been implicated in not only kidney stones, but also pelvic pain issues such as interstitial cystitis and vulvodynia.

Nearly 90% of women with interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome (IC/BPS) report sensitivities to a wide variety of dietary components. Current questionnaire-based literature suggests that citrus fruits, tomatoes, vitamin C, artificial sweeteners, coffee, tea, carbonated and alcoholic beverages, and spicy foods tend to exacerbate symptoms, while calcium glycerophosphate and sodium bicarbonate tend to improve symptoms. Case reports have demonstrated that modification of oxalates in the urine through low oxalate diet and gut binders for oxalates such as calcium citrate may be beneficial to alleviate symptoms.

How does the body process oxalates?

When we eat foods with oxalate, it travels through the digestive tract and passes out in the gastrointestinal tract or is processed by the kidneys. As it passes through the intestines, oxalate can bind with calcium and be excreted in the gut. However, when too much oxalate continues through to the kidneys, it can lead to kidney stones and other health issues

What causes oxalate buildup?

Foods that are high in vitamin C can increase the body’s oxalate levels. Vitamin C converts to oxalate. Levels over 1,000 milligrams (mg) per day have been shown to increase oxalate levels.

Taking antibiotics, or having a history of digestive disease, can also increase the body’s oxalate levels. The good bacteria in the gut help get rid of oxalate, and when the levels of these bacteria are low, higher amounts of oxalate can be absorbed in the body.

Recent data indicates that boosting your intake of calcium-rich foods when you eat foods that are high in oxalate may be a better approach than simply trying to eliminate oxalate from the diet.

In research studies, some individuals have been shown to be "hyperabsorbers" of oxalate from the intestinal tract. In other words, their bodies uptake more oxalate than would normally be expected. In principle, the greater the amount of oxalate that gets absorbed into the body, the greater the amount that will reach the kidneys and raise the level of urinary oxalates.

Our gut bacteria turn out to play a critical role in the amount of oxalate available for absorption since numerous species of gut bacteria are able to break down oxalate. These species include Oxalobacter formigenes, numerous species of Lactobacillus, and several species of Bifidobacteria. In fact, a good number of studies are underway to investigate the role of oral probiotic supplements and their impact on oxalate absorption.

Research has shown that the overall combination of foods that we eat during a meal (including both oxalate-containing and non-oxalate-containing foods) can significantly impact the amount of soluble oxalates available for absorption from our digestive tract. We've seen a study on Indian cuisine, for example, in which multiple-ingredient dishes like spinach (palak) also containing Indian cottage cheese (paneer) lowered the amount of soluble oxalates available for absorption by about 15-20%.

Oxalates and the gut microbiome

In recent years, it has also been acknowledged that gut commensal bacteria with oxalate-degrading activity have the potential to contribute to oxalate homeostasis.

While much of the work has focused on the role of the intestinal bacterium, Oxalobacter formigenes, an oxalate-degrading specialist, recent metagenomic studies show that oxalate homeostasis is maintained more by a symbiotic community of bacteria rather than isolated species.

Oxalobacter formigenes (Oxf) is part of the normal gut flora in humans and other mammals. It actually requires oxalate for survival. It degrades ingested oxalate, reduces intestinal absorption, and fuels oxalate secretion from the colon, offering protection from hyperoxaluria.

Studies reveal that probiotics can decrease urinary oxalate excretion, at least temporarily. The formulas include Oxf alone, or different combinations of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and other oxalate degraders.

One small trial assessed whether a 4-week daily consumption of a probiotic supplement would decrease oxalate absorption in 11 healthy volunteers. The results showed that in high oxalate absorbers, VSL#3 (a mixture of high concentrations of eight different bacteria) has the potential to reduce oxalate absorption.

In order to observe the role of microbiota gut samples from individuals have been analyzed for bacterial oxalate degrading activity, bacterial diversity, and relative species abundance. This is what was found in the low oxalate group more oxalate degradation; higher fecal Lactobacillus diversity; more Bifidobacterium spp.were found. Interestingly, Oxf was present only at very low levels in both groups.

Oxalate degradation is likely a function of a network of bacterial species and defining that matrix should provide valuable therapies for concerns associated with high oxalate levels.

Although the intestinal microbiome seems likely to play a role to modify gastrointestinal absorption of oxalates, the tools to manipulate it and decrease oxalate levels remains to be determined.

Probiotics

Oxalobacter formigenes (O. formigenes) is a nonpathogenic, Gram-negative, obligate anaerobic bacterium that commonly inhabits the human gut and degrades oxalate as its major energy and carbon source.

Other bacteria may play a role in oxalate degradation in the intestines, including Eubacterium lentum, Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Bifidobacterium lactis.

Currently, there were no well proven probiotic supplements with O. formigenes,

VSL 3 may be beneficial

Currently, there were no well proven probiotic supplements with O. formigenes,

Liebman & Al-Wahsh reviewed the research on the probiotic supplements that have been tested to see if they reduce oxalate load. There were 6 studies, but they were fraught with different variables. Positive results were obtained by using the VSL#3 preparations from the company Oxadrop. Their current preparation of VSL#3 contains:

Bifidobacterium breve

Bifidobacterium longum

Bifidobacterium infantis

Lactobacillus acidophilus

Lactobacillus plantarum

Lactobacillus paracasei

Lactobacillus bulgaricus

Streptococcus thermophilus

This preparation taken at a dose of 800 billion bacteria, once a day, dissolved in water after the last meal of the day for 4 weeks, reduced urinary oxalate excretion by 33%. A follow-up test compared a 450 billion dose of VSL#3 to a 900 billion and found better results with the 900 billion but it wasn’t statistically significant.

The use of certain antibiotics is the main factor affecting colonization with O. formigenes among U.S. adults. Compared with nonusers, a markedly lower prevalence of colonization among individuals who, in the last 5 years, had taken antibiotics to which the bacterium has been reported to be sensitive, including macrolides, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, rifampin, and metronidazole has been observed.

Oxalates and calcium

Calcium carbonate and calcium citrate supplements are both useful for binding oxalate in the gastrointestinal tract, calcium citrate supplements are recommended as they seem to help kidneys excrete urinary citrate.

A 2004 study from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center tested potassium citrate, calcium citrate (400 mg of calcium twice a day), and a combination of each for 2 weeks on women who were not kidney stone formers. Calcium citrate lowered oxalate excretion while potassium citrate lowered calcium-oxalate saturation.

Oxalate content of foods

The oxalate levels reported in foods can vary depending on the following factors:

when the foods are harvested

where they are grown

how their oxalate levels were tested

High-oxalate foods Foods that are highest in oxalate include:

fruits

vegetables

nuts

seeds

legumes

grains

High-oxalate fruits include:

berries

kiwis

figs

purple grapes

Vegetables that contain high levels of oxalate include:

rhubarb

okra

leeks

spinach

beets

Swiss chard

To reduce how much oxalate you get, avoid:

almonds

cashews

peanuts

soy products

Some grain products are also high in oxalate, including:

bran flakes

wheat germ

quinoa

The following foods are also high in oxalates:

cocoa

chocolate

tea

Most fruits and vegetables contain measurable amounts of oxalates in the small-to-moderate range.

Parsley is also worth mentioning here at about 100 mg.

A note about the oxalate content of lemons and limes: as indicated above, the peels of these fruits have been analyzed as high in oxalate content. However, the juice of these fruits (e.g., lemon and lime juice) is not only low in oxalates, but also high in other organic acids called citrates. Research suggests that the high citrate content in lemon and lime juice might actually help lower risk of calcium oxalate kidney stone formation. By binding together with calcium in place of oxalates, citrates can help reduce risk of urine supersaturation with calcium oxalate.

High-calcium foods

Increasing your calcium intake when eating foods with oxalate can help lower oxalate levels in the urine. Choose high-calcium dairy foods such as milk, yogurt, and cheese. Recent studies indicate that boosting your intake of calcium-rich foods when you eat foods that are high in oxalate may be a better approach than simply eliminating it from the diet.

Vegetables can also provide a good amount of calcium. Choose among the following foods to increase your calcium levels:

broccoli

watercress

kale

High-calcium legumes that have a fair amount of calcium include:

kidney beans

chickpeas

baked beans

navy beans

Fish with a lot of calcium include:

sardines with bones

whitebait

salmon

The effect of cooking on oxalates

Cooking has a relatively small impact on the oxalate content of foods. In fact, we've seen one recent study examining oxalate changes in 20 different green leafy vegetables in cooked versus raw form which found no significant changes for any of the 20 vegetables.

The low oxalate nutrition plan

On a low oxalate diet, you should limit your oxalate to 40 to 50 mg each day. Oxalate is found in many foods. Your body may turn extra vitamin C into oxalate. Avoid high doses of vitamin C supplements (more than 2,000 mg of vitamin C per day)

On a low oxalate diet, you should limit your oxalate to 40 to 50 mg each day. Oxalate is found in many foods. The following charts will help you avoid foods high in oxalate. They will help you eat foods low in oxalate.

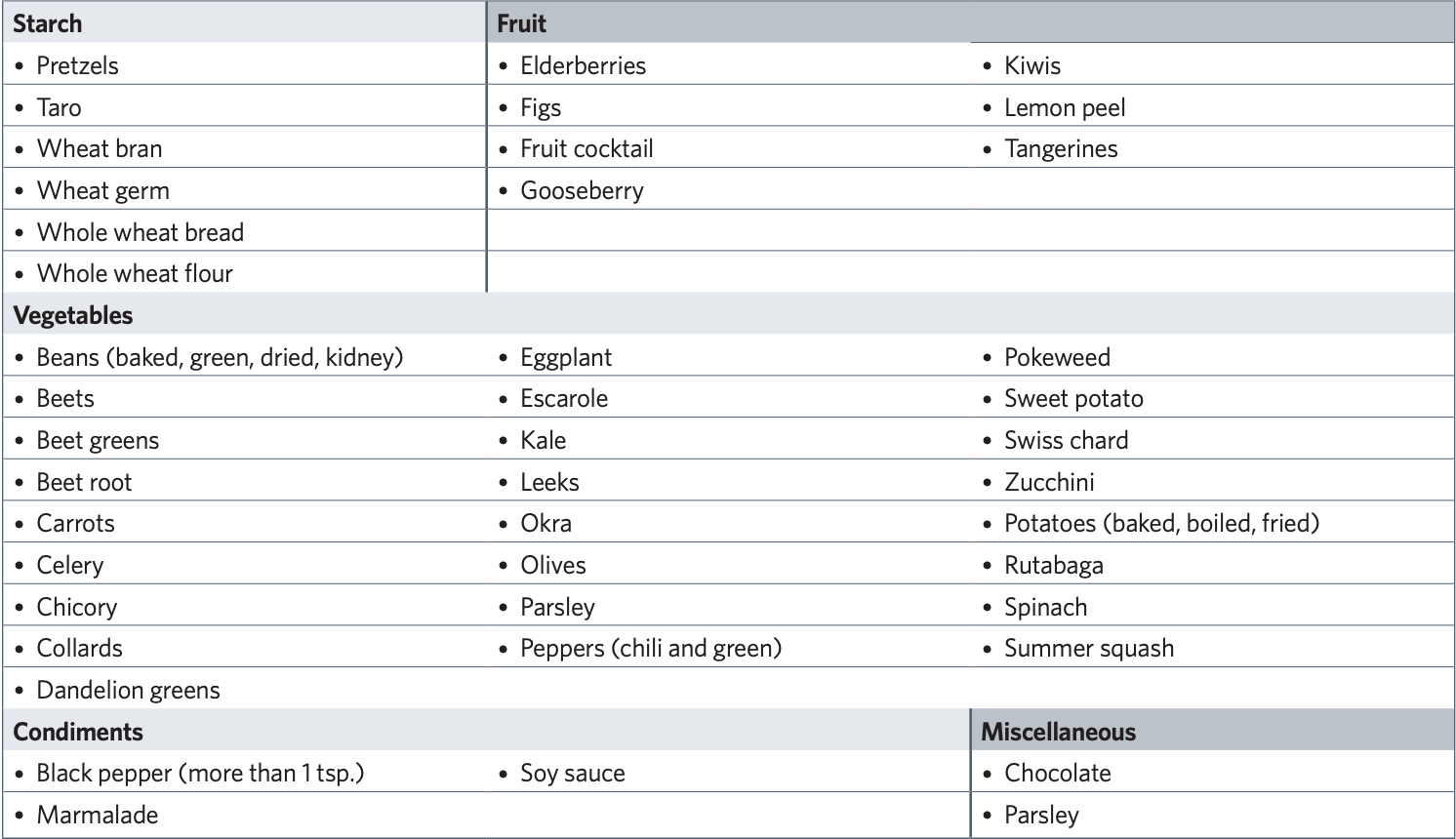

Avoid these High-oxalate Foods and Drinks High-oxalate foods have more than 10 mg of oxalate per serving.

Limit these Moderate-oxalate Foods and Drinks You should have no more than two or three servings of these foods per day. Moderate-oxalate foods have 2 to10 mg of oxalate per serving.

Enjoy these Low-oxalate Foods and Drinks Eat as much of these low-oxalate foods as you like. Low-oxalate foods have less than 2 mg of oxalate per serving.